Scarlett Loran opened tonight’s mass – a quintessentially online ingénue who looks like she’s been pulled straight from the algorithm’s imagination. Hailing from somewhere that feels like a Tumblr blog and sounds like the moon singing back to itself, she floated on stage with the kind of coy banter that walks the tightrope between indie darling and cosmic trickster.

Playing alongside The session keyboardist (who, by the way, met Scarlett Loran just hours earlier in a hotel lobby like some rom-com subplot). “This next one’s about the moon,” she told us, before admitting it was actually about her boyfriend. Suki Waterhouse would nod in approval. Standout tracks like “Tide” and “Silver Microscope” made it clear – she’s not just a pretty tweet, she’s a poet in 70’s bohemian threads.

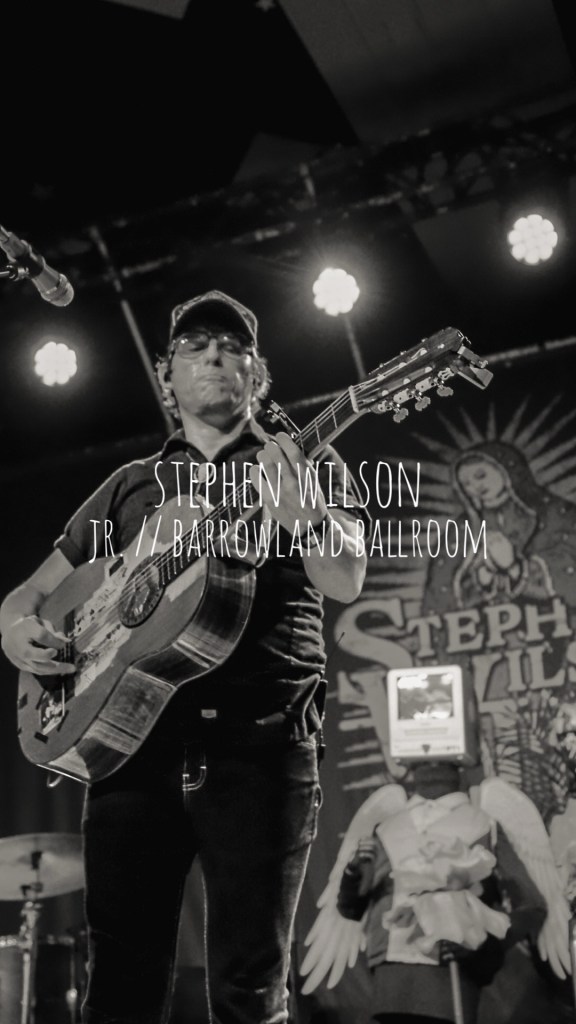

But the main sermon tonight came from Stephen Wilson Jr. – a man who looks like he’s been carved from Kentucky oak and sings like he gargled gravel in the Garden of Gethsemane. I’ll admit, I walked into the Barrowlands tonight curious but unconvinced. Could this bourbon-soaked balladeer really translate his studio grit into something as raw and alive as Glasgow? Spoiler alert: yes. With the subtlety of a crowbar and the grace of gospel, he not only translated it – he set it on fire.

The set opened with “Preacher’s Kid” – a wild, grinning, full-band explosion of Southern gothic sincerity. The crowd roared his name like it was a war cry: “Stevie! Steeeeevie!” In that gloriously guttural Glaswegian way that makes you feel like you’re part of something ancient and tribal.

“Billy” came next, a song that feels like Neutral Milk Hotel took a road trip through Appalachia with a flask full of heartbreak and a notebook of unfinished poems. Wilson introduced it with a story – one of many – revealing a natural ease on stage that only comes from bleeding on small-town barroom floors for years. “Hillbilly,” he mused. “Where I’m from, it wasn’t a compliment. But let’s reclaim it.” It was part jovial banter with a new friend you’ve just bought a drink for at the bar, part sermon, part therapy – and the audience were the devout.

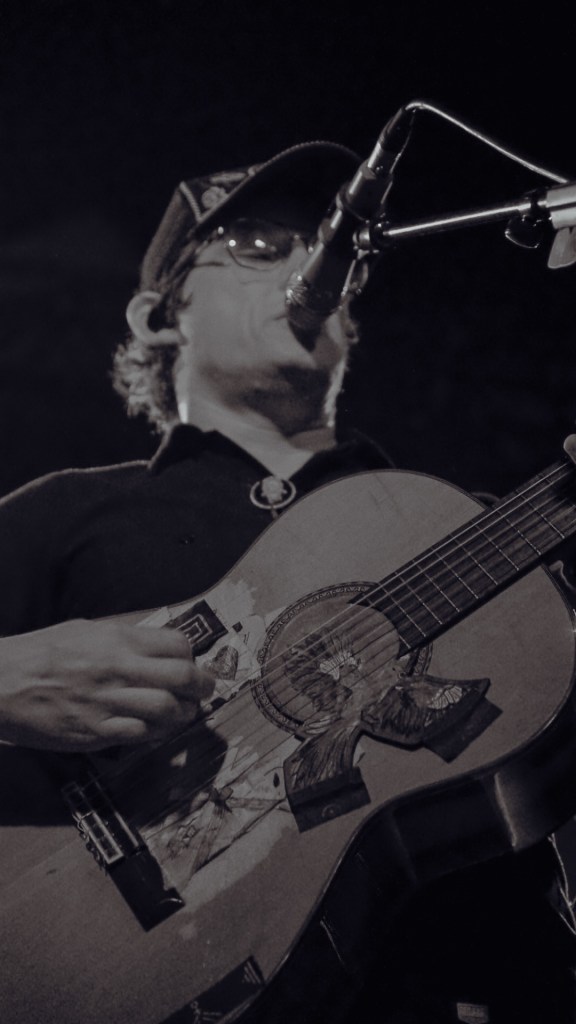

Then came “Patches” – “for anyone who has a hole in them… or a hole in their guitar,” he quipped with a crooked grin. And just like that, laughter and lump-in-the-throat living side-by-side. Gratitude, grief, acceptance – these weren’t just themes, they were liturgies.

His band – a ragtag ensemble of Americana Avengers – deserve their own mention; Scotty Murray – a lap steel whisperer who looked like he’d fallen out of a Fleetwood Mac tour van, Miles Burger on bass guitar and sitar-sorcerer straight off a Reddit forum for cosmic twang, and a drummer Julian Dorio on awho played like the ghost of Levon Helm had possessed him mid-gig.

“The Devil” was the song that started it all. Written at 3:30 a.m. after the death of his father, funded by a $333 life insurance cheque, it’s not just a track – it’s a resurrection. You could hear the cashing of grief into purpose in every note.

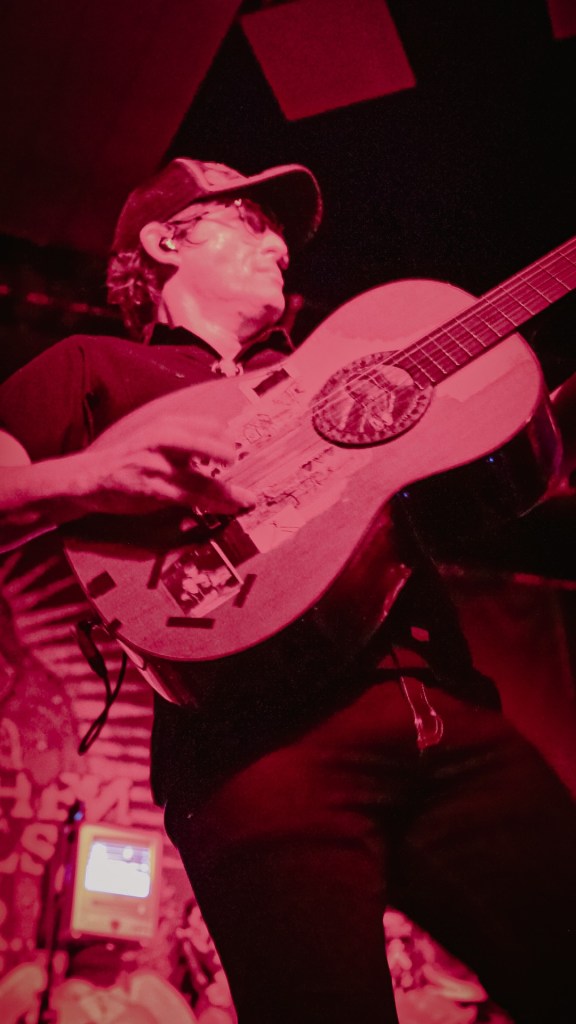

Later, “Father’s Son” turned the room into a shrine. Phones lit the air like votive candles. “I always introduce myself to strangers the same way, with my thesis which is ‘Hi, I’m Stephen Wilson Jr and I am my fathers son… My father passed away 6 years ago and I try to keep him alive through music” he said – and we believed him.

The kind of belief that makes you reach for your own memories and hold them close. With my own father’s anniversary looming, it hit like a freight train – but one driven by kindness and catharsis.

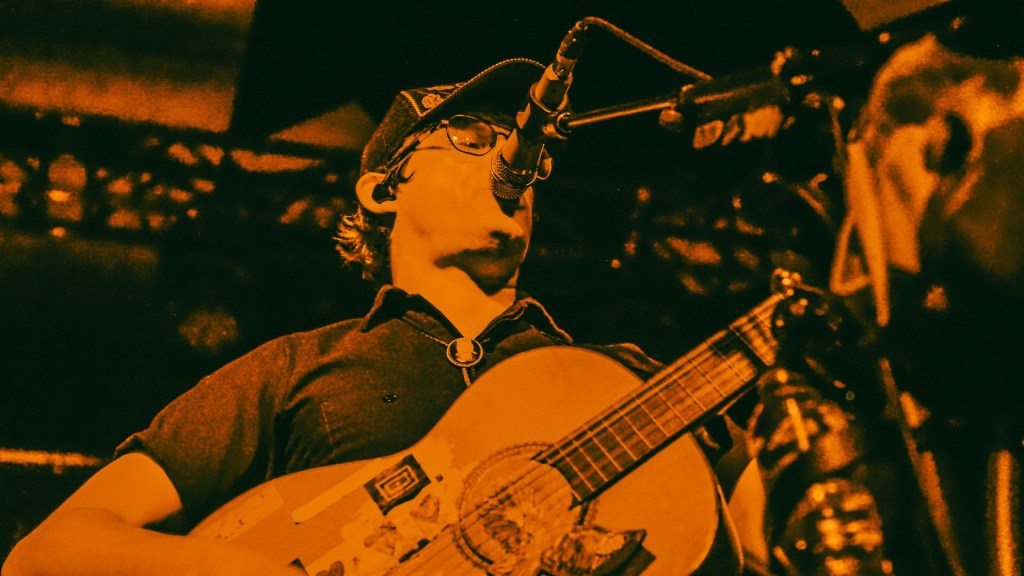

And then there were the covers. His take on “Stand By Me” wasn’t just a tribute, it was a total transfiguration. Imagine if Hozier and Chris Stapleton got drunk on empathy and decided to raise the spirit of Ben E. King for one more chorus. The crowd responded the only way Glaswegians know how: “Here we, here we, f*cking go! Steeeeveeee!”

His rendition of Something in the Way brought the ghost of Kurt Cobain to the ballroom – haunting, brittle, beautiful. Nirvana by way of Nashville, filtered through heartbreak and hope.

Then came the kiss-off love song for the skatepark romantics: “Year to Be Young 1994”. He told us he wrote it after meeting his girlfriend. “This is for anyone who’s ever gone teeth-first into a kiss,” he joked, and we howled because, let’s be honest, we’ve all been there.

The encore arrived reluctantly – the band didn’t want to leave, and we weren’t about to let them. They returned to foot-stamping adoration with “I’m a Song”, a meta anthem about being the art you make and surviving because of it. And finally, “Gary” – a track that plays like Bruce Springsteen sharing secrets with Father John Misty in a Waffle House at 2 a.m. It was wry, wounded, and weirdly joyful – a perfect closer.

As he left the stage, Stephen promised to return sooner next time. We believed him.

I came expecting a decent gig. I left feeling like I’d been to a wake and a wedding and a backwoods revival all at once. For a show built on grief, this was one of the most life-affirming nights I’ve experienced in years. In a world that often forgets how to feel, Stephen Wilson Jr. reminds us that music is still the best way we have to stitch ourselves back together – one bourbon-soaked ballad at a time.

Article: Angela Canavan